By William Roulett

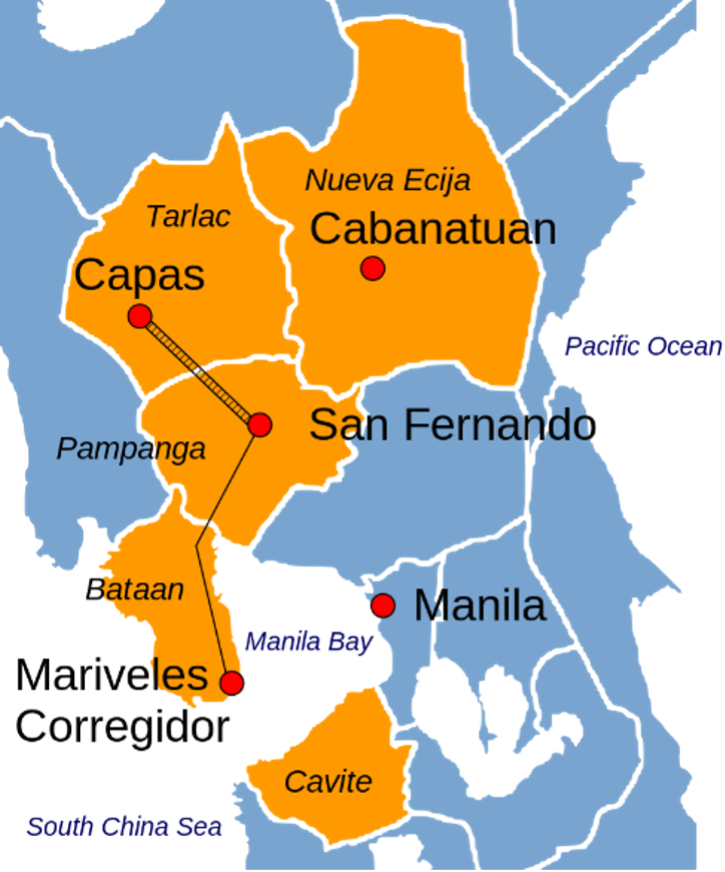

April 9, 2022, marks the 80th anniversary of the start of the Bataan Death March. Orchestrated by the Imperial Japanese Army, some 60,000-80,000 American and Filipino Prisoners of War (POWs) were brutally forced to march more than 60 miles from Mariveles, at the southern end of the Bataan peninsula, to Camp O’Donnell in Capas, Tarlac Province. Among the American captives was Capt. Edward Lingo of the New Mexico National Guard’s 200th Coastal Artillery (Anti-Aircraft), which arrived in the Philippines in September of 1941. The National Guard Memorial Museum is honored to have his journal on display in the WWII gallery.

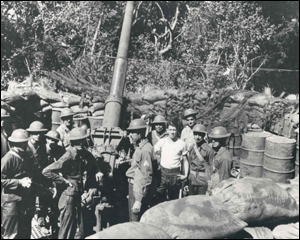

The US mobilized the National Guard as tensions rose around the world prior to America’s entry into World War II. The 200th Coastal Artillery was chosen for the deployment because of the unit’s large number of Spanish speakers. They were joined in the Philippines by the 515th Coastal Artillery (New Mexico National Guard), 192nd Tank Battalion (Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, and Kentucky National Guards), and 194th Tank Battalion (California, Minnesota, and Missouri National Guards). These units worked to defend the island with other Americans and Filipinos.

World War II began for the 200th at 0300 on December 8, 1941, Manila time (0900 on December 7, Hawaii time) when they learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor via radio broadcasts. In the coming weeks, the 200th became one of the first American units to see combat. Lingo began keeping his journal the same day his war started, keeping meticulous track of his weight loss over the course of over three years in captivity.

(Courtesy of April – Today in Guard History – The National Guard)

In our museum, you can read the pages of Capt. Lingo’s journal that chronicle the days leading up to the Bataan Death March. He wrote about food shortages, how hunger and exhaustion made simple tasks more difficult, bombings, and some thoughts about General Douglas MacArthur. However, despite the dire situation, Capt. Lingo was grateful for a priest who had recently joined the unit and was able to perform a Catholic Mass on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1942.

The 200th and most other allied forces in the Philippines surrendered on April 9. They were subjected to savagery during a forced march of over 60 miles. The wounded and malnourished condition of many prisoners was compounded by physical abuse at the hands of their Japanese captors. Almost 700 Americans and far more Filipinos died during the march. Of the 1,800 New Mexico National Guardsmen that deployed to the Philippines, only 900 would return to New Mexico.

(Courtesy of April – Today in Guard History – The National Guard)

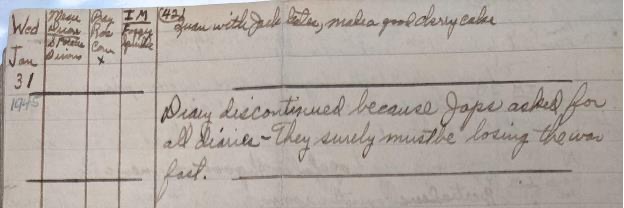

During Capt. Lingo’s time in captivity, he endured the Bataan Death March and was transported to Zentsuji prison camp in the Kagawa Prefecture, on the Japanese home islands. His journal ended abruptly on January 31, 1945, when guards confiscated diaries, which prompted Lingo to speculate that the Japanese were losing the war.

Edward Lingo survived the war, rising to the rank of Lt. Col., passing away on February 23, 2001, at the age of 88. If you want to learn more about the heroism and contributions of the New Mexico National Guard, visit the New Mexico Military Museum. To see Capt. Lingo’s journal and more about the history of the National Guard throughout American history, visit the National Guard Memorial Museum.