By Abby Learner

Captain Edward Lingo

(Courtesy of the New Mexico Military Museum)

The National Guard Memorial Museum is proud to have on display the diary of Captain Edward Lingo of New Mexico’s 200th Coast Artillery, one of the first American units to see combat in WW2. Capt. Lingo served, alongside almost 2,000 other Guardsmen from the same unit. This diary is on loan from the New Mexico Military Museum along with other artifacts. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, American bases in the Philippines were bombed by the Japanese. On April 9th of 1942, by order of General Douglas MacArthur, American troops in the Philippines surrendered to the Japanese. This was the largest American surrender in history. Lingo’s diary gives us a candid and intimate look into his life from 1941 to 1945, from the attack on Pearl Harbor through his experiences in the Philippines before capture, to his harrowing survival of the infamous Bataan Death March and his subsequent experiences as a POW.

The Diary is split into 2 volumes, each extremely different and telling of his deteriorating mental and physical condition. The first volume of the diary is on display in our museum and has been transcribed. Click on link to see full transcription. Diary 1 traces his experiences in the Philippines from the moment the news breaks about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, through the invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese, to the American surrender and Bataan Death March. The second half of the diary details his capture, the terrible conditions, and the horrific sights he witnessed on the march.

Even though he describes periods of exhaustion, hunger, and the horrors of war, we can tell that Lieutenant Lingo understood the importance of keeping a diary and wanted to be able to share his story with future audiences. We at the National Guard Memorial Museum are honored to have the opportunity to make his diary available to the public.

The diary starts on the same day of the attack on pearl harbor at approximately 12:50 pm, on Dec 8th, 1941 (Philippines time). Lingo states on page 1 that he was assigned to Battery H of the 200th Coast Artillery, located at Fort Slotenberg, which was about 60 km north of Manila. Battery H was part of 3rd platoon and located about 100 yards north of Clark airport.

Lingo described the surprise attack, December 8th Philippine time:

“…was playing solitaire listening to the 12:30 pm news broadcast about Baguio P. and Hawaii being bombed to when Lt Frank Turner said this was a big formation (54 planes) of bombers coming from the northwest. I hurried but to the door not… All of a sudden it dawned on me they might be dropping bombs and about that time these bombs started hitting the ground.”

The 200th spent months moving positions in an effort to stop the Japanese until April 9th, the men were told that they would no longer be moving. In the week leading up to April 9th, desperate and seemingly unorganized attempts were made to move to new positions as the Japanese were closing in. Lingo describes the moment the men are informed of their surrender below:

“About 4:30 A.M. we were awakened… and…our battery commander instructed us… to form a new line…In the meantime he had been informed that we had surrendered, to turn in all our arms, ammunition, knives, etc.…”

The next day they were instructed to go to the airport where he encountered a Filipino Scout Master Sergeant:

“With tears in his eyes, he said, ‘after being in the army for 34 years this is what happens.’ One of the saddest things I have ever witnessed.”

The men waited, defenseless and uncertain what was in store for them. Lingo wrote that during the day Jap bombers would fly overhead and occasionally drop a bomb or two. Lingo commented that it made them “feel funny as we had no arms to fire back with”

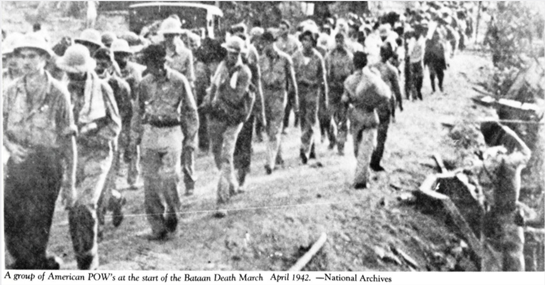

“A group of American POW’s at the start of the Bataan Death March. April 1942 – National Archives”

(Courtesy of History National Guard of New Mexico 1606-1963)

Upon arriving at the airport, the Japanese took their trucks away and told the men to start marching. This was the introduction to what life was going to look like for the indefinite future. Lingo described his experience when the Japanese stripped him and his men of all of their personal belongings.

“…I had my wrist watch taken, then a little while later my knife, pocket watch, pocket book even took my toothbrush and put it in his mouth. They went through my field bag at different times taking my canned rations, clothes, etc finally taking the bag and all. Also they took my blanket and shelter half. Took my canteen full of water & returned me an empty one.”

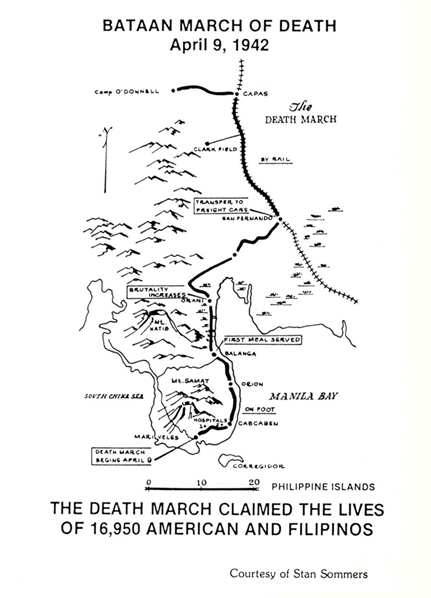

Bataan March of Death

(Courtesy of From Bataan to Freedom by Judy Reed)

The surrender of the American and Filipino troops meant that there were now tens of thousands of men in limbo. With an overwhelming number of men that needed to be moved to POW camps, the Japanese forces led the men on a treacherous march to camp O’Donnell. This march would later come to be known, as named by the survivors, as the infamous Bataan Death March. It was a brutal 60 plus mile march that lasted about 6 days. Approximately 60,000-80,000 American and Filipino POWs were forced to march to Camp O’Donnell. Thousands of POWs did not survive the trip due to the brutal nature of their march. They were given no food or water. If men couldn’t carry on any longer, they fell out of line or collapsed, they were immediately shot and killed or subjected to abuse. Lingo describes one specific incident from the march and a violent encounter with a high-ranking Japanese officer who saw ill men resting:

“ Most everyone fell in line but the sick that were lying aside grouped together could not make it so he picked up a big piece of bamboo and started hitting these fellows over the head with a mighty blow. I saw one fellows head split open… and here we were standing in line unable to do a thing about the abuse.”

Blatant disrespect, getting physically slapped in the face, and watching men be tortured became routine as a POW. Once the men reached San Fernando en route to Camp O’Donnell, they were piled into box cars not fit for any human and with no knowledge of their destination. Lingo, many times throughout his writings, constantly compares the treatment of his men to that of sheep, emphasizing the dehumanization of prisoners:

“we were placed in a small (steel) box car, 120 of us… and the doors closed. We didn’t have room to turn around much less sit down. It was terribly hot & the men were getting sick and most of us had diarrhea…. Again I say it was criminal. We were just sheep not even good sheep in their eyes and not even good sheep”

(Courtesy of History National Guard of New Mexico 1606-1963)

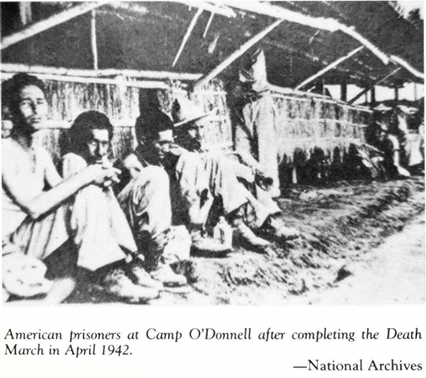

On April 17th 1942, Lingo arrived at Camp O’Donnell with fewer men than had started the Death March. From his battery of 68 men, only 51 arrived. Once there, 5 men were suspected of carrying Japanese property and were punished. Lingo says that these men were taken and never seen again.

Malnourishment was a constant. The food at O’Donnel for the first 10 days consisted of ¾ of a canteen of Lugo, which is a thickened rice soup. Lingo made note of the rapid weight loss of the men, with many men who started out weighing 200 pounds now down to 110 pounds and sick with dysentery. They were “nothing but skin and bones.” Lingo shares:

“We had 22 men die in the 1st 14 days. They died of exhaustion due to lack of food and the hardship”

According to Lingo, there were a total of 9,000 American prisoners and about 40,000 Filipino prisoners. Filipino prisoners, he says “were dying at the rate of 400 a day”. Lingo describes himself as incredibly lucky to have maintained his health most of his time there. In the camps, malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and dysentery were rampant. The lack of quinine, used to treat malaria, was especially detrimental. The quote below encapsulates the severity of disease in the camps, specifically malaria:

“Men often slept at the latrine because they did not have the strength to move away from it. I saw boys just burn up with malaria fever. Often the thermometer registered 105.5 to 106. I actually saw boys just plain burn up & die with fever because we could not get quinine till June 2nd we had 1600 men out of 9000 die. They were buried in groups of 6 to the grave. Most of the boys were hardly able to dig the grave for the dead ones. The hospital had no facilities at all. No beds, blankets, medicines. It was terrible. Just a little quinine would have saved many.”

Edward Lingo survived the war and continued to serve, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His story of bravery and perseverance lives on through his diary. We are incredibly lucky to have this rare resource courtesy of a survivor himself, which can be seen on display at the National Guard Memorial Museum. Find the diary and transcription here.