By: Jacob Paulsen

The Spark to Unrest

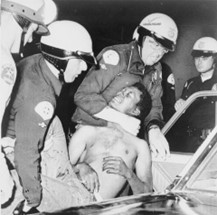

On the night of Wednesday, August 11, 1965, when Marquette Frye was pulled over for suspected drunk driving, the officers at the scene were unaware of the ensuing chaos. The traffic stop soon escalated, and a crowd of 50 people watched as Frye failed sobriety tests and then resisted arrest. Police responded violently as the crowd continued to swell to over 1,000 people. The next six days left 34 people dead, over 1,000 injured, 3,500 arrested and cost the city $40 million in damages.

The Watts Riots were declared an emergency by Acting Governor Glenn Anderson when local police were unable to contain the situation. Acting under his executive authority, Anderson mobilized the State’s National Guard on August 13, 1965.

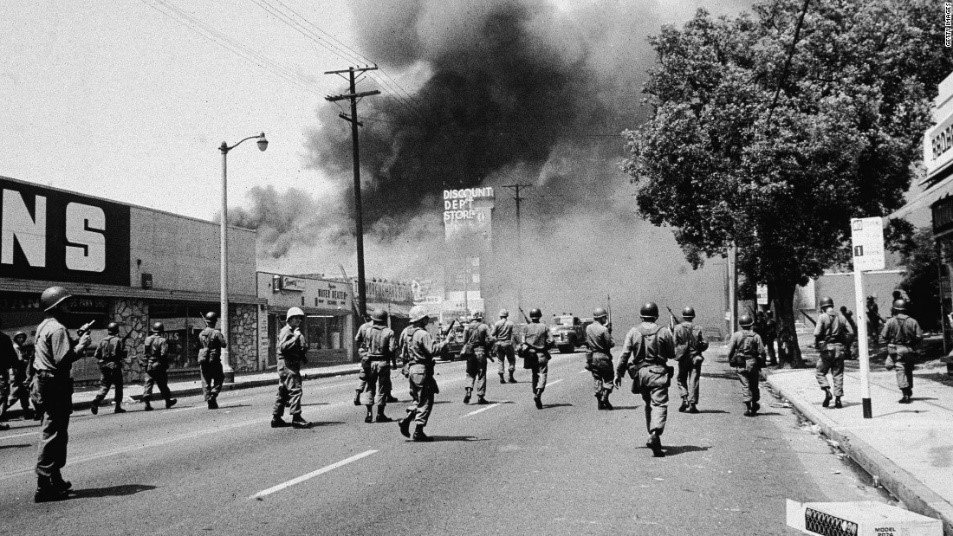

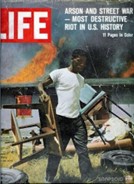

California’s National Guard was mobilized to suppress what LA Police Chief William Parker described as an insurrection akin to the “Viet Cong.” These troops were tasked with quelling what would become the city’s worst riots until the officers charged with beating Rodney King were acquitted in 1992 (Hinton 68). The Watts Riots are a chapter in a long history of racial tensions. Its legacy was documented through the new age of photography and defined rising civil unrest. But these six days cannot be separated from the deeper realities of life in Los Angeles.

(Courtesy of Showbiz)

Background to the Riots

In the years leading up to the Watts Riots, disparity existed between White and African American Los Angeles citizens. The city had become a popular destination during the Great Migration, when six million African Americans migrated from the South to the North and West in search of improved economic and social opportunities. The African American population of Los Angeles increased from 63,700 in 1940 to 365,000 in 1965. However, as the urban environment transformed, African Americans did not prosper from access to opportunities promised by the American Dream.

This systemic inequality created an environment where frustration quickly turned into unrest. That unrest erupted into violence that ultimately necessitated the California National Guard.

Mobilization of the Guard

Although rioting persisted from August 11-12, the California National Guard was not mobilized until 10:00 pm on August 13th.

These Guardsmen were expected to be prepared for rioting throughout California. In July 1964, the California Military Department directed the California Army National Guard to receive two additional hours of riot training beyond the national standard of three hours.

Once they arrived, the police were concerned about two areas. The first was a section of the Watts District, and the other was a stretch of Avalon Boulevard.

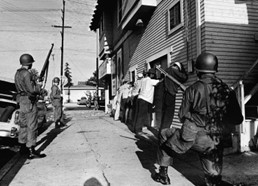

The police gave the National Guard the mission of taking control of these areas. The Guard aimed to apprehend rioters, prevent looting, and secure life and property. Colonel Irving B. Taylor, Commanding Officer of the 2nd Brigade, 40th Armored Division, was placed in command of the Guard troops during the operation. The 49th Infantry Division of the California National Guard, would join later.

As the crisis intensified, Acting Governor Anderson proclaimed a State of Extreme Emergency in Los Angeles County at 4:45 pm on August 14th. Anderson implemented a curfew, keeping people off the streets in certain areas after 8:00 p.m. Around this same time, California’s Adjutant General Roderic L. Hill, decided that the full resources of the 40th Armored Division and most of the 49th Infantry Division would be committed to riot control operations. Finally, on the night of August 15th, a total of 13,400 Guardsmen were deployed in and around the curfew area. By the morning of August 16th, the Guard had stabilized the situation.

The Guard contained the riots and maintained control of key areas under police direction, aiming to avoid the appearance of a militarized neighborhood. While their actions were widely successful, they did not avoid controversy.

Officials did not alert the Guard on August 12th and they did not mobilize until the late evening on August 13th after rioting escalated. The delay raises a question: was the guard delayed because of over-cautiousness or to avoid controversy? [NI1] Either way, the riots in Los Angeles demonstrated the risks of allowing unrest to escalate. Over the following five years, the National Guard was mobilized in more than 260 instances to maintain order alongside state and local police. In the twenty years before 1965, that number was eighty-eight.

The Community’s View

Shifting perspectives, for many people who lived in the Watts District, the riots were a form of protest rather than an insurrection. A 1968 series of interviews reported that 34% of African Americans living in the Los Angeles area supported the riots (Sears).

This highlights the narrow line dividing perspectives on National Guard involvement. Some citizens from the Watts District viewed the National Guard unfavorably due to its involvement in anti-riot operations. However, Police Chief William Parker observed the chaos and decided that the riots would become more dangerous if the law was not enforced. He told Colonel Quick of the California National Guard, “[we can] no longer maintain control and prevent further bloodshed, violence and damage” (Hartt).

(Courtesy of The Mercury News)

Lessons for a Modern Era

Looking back sixty years later, the Watts Riots can offer a different lens through which to view civil unrest today. The Guard dealt with the complex task of protecting public safety while maintaining responsibility to state and federal authorities.

Over 30,000 National Guardsmen were called up in response to political unrest and violence in 2020. This was in addition to the 40,000 National Guardsmen already deployed in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, the largest mobilization since the civil rights movement. As the nation responded, the Guard once again faced the arduous task of balancing order with justice.

From the Watts Riots through today, Guardsmen have carried the heavy responsibility of confronting unrest, only to return home to their communities. Their action embodies the legacy of the Guard as both citizen and soldier.

Bibliography

Hartt, Julian. “Riot Duty: The California National Guard at Watts.” The National Guardsman, Oct. 1965.

Hinton, Elizabeth. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime the Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Oberschall, Anthony. “The Los Angeles Riot of August 1965.” Social Problems, vol. 15, no. 3, 1968, pp. 322–41. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/799788. Accessed 22 Sept. 2025.

SEARS, DAVID O., and T. M. TOMLINSON. “Riot Ideology in Los Angeles: A Study of Negro Attitudes.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 3, 1968, pp. 485–503. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42858410. Accessed 22 Sept. 2025.