SFC Aaron Heft, MDARNG Historian

By the mid-1700s, Maryland was a well-established part of the British colonies, with a burgeoning trade flowing from its ports and coastline. Farmers cultivated the colony’s fertile soil to grow tobacco, corn, and grains, and by the 1760s, Maryland was dotted with large plantations and small tenant farmers. Developing cities like Annapolis and Baltimore gave the colony a growing urban population.[1] Considered a “middle colony,” Maryland served as a bridge between the southern and northern economies. In the late 18th century, Marylanders were no strangers to discontent with the crown’s administration of their colony. The heavy dependence on trade through the port of Baltimore meant that taxes and restrictions had a disproportionate effect on Maryland’s economy, much like that of Boston to the north. As the colonies moved closer and closer to outright conflict with England, many Marylanders became outspoken critics of English policies.[2]

Discontent across the colonies flared with events like the Boston Tea Party or Maryland’s own burning of the Peggy Stewart in 1774.[3] When the British Crown dissolved the Maryland Assembly in 1774, the Convention of Maryland was tasked with running the colony and called for a revitalization of the state’s fledgling militia. On December 3rd, 1774, in Baltimore, merchant and revolutionary advocate Mordecai Gist chartered the “Baltimore Independent Cadets,” a 60-member militia company that quickly set to preparing for the city’s defense. Recruited from the city’s wealthy merchant class, the men outfitted themselves with weapons, uniforms, and equipment under the guidance of a veteran of Boston’s Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. They set to drill and prepare for the coming conflict, making public their intent to defend Baltimore and its environs. While Gist’s Cadets would see no combat action, they would provide the leadership for many of Maryland’s future field units.[4]

By the summer of 1776, the troubles in the colonies had progressed to open warfare, and the Maryland Convention authorized the formation of a battalion to join the embattled Continental troops under George Washington, then encamped in New York. Colonel William Smallwood, a veteran of the French and Indian War, was elected to lead the battalion, and many members of the Independent Cadets, including Gist himself, would make up the battalion leadership, spread across nine companies.[5] Arriving in New York in July 1776, the Marylanders joined Washington’s defenses. A 17,000-man force manned fortifications in New York City, Brooklyn, and Long Island, awaiting the advance of a large British force. It would only be a short while until the Maryland Battalion proved its worth. In late August 1776, combined British and Hessian forces under General William Howe landed on Long Island and approached Washington’s defenses through the unguarded Jamacia Pass.[6]

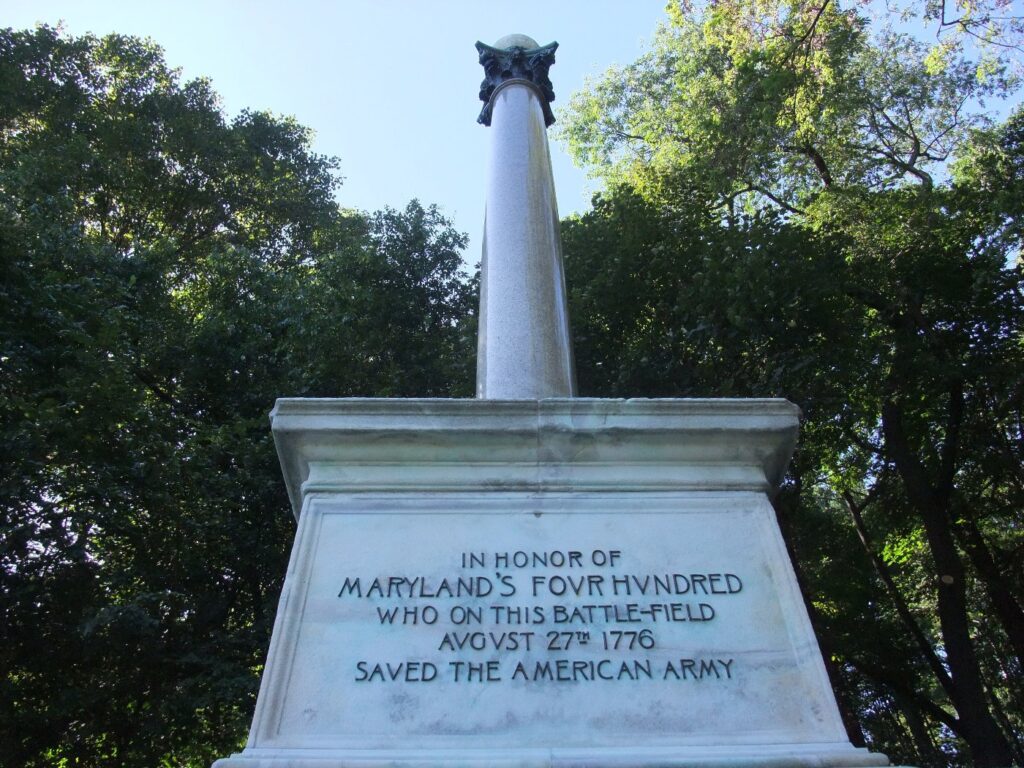

The Continental Army’s performance during the initial stages of Long Island was somewhat disappointing. On the morning of August 27th, Howe’s force assaulted the left flank of American lines and rapidly defeated their defenses. Desperate fighting raged across the Island, and after a morning of sustained combat, the Continentals found themselves outflanked and nearly surrounded by British forces. The battle was shaping up to be a catastrophic defeat, and the Continental Army would need to evacuate the bulk of their force back to Brooklyn to ensure their ability to fight another day. In this dark hour, the 1st Maryland Regiment, one of the few outfits in the army equipped with bayonets, was ordered to launch a lone counterattack into the advancing British troops. The approximately 400 remaining Marylanders, headed by Mordecai Gist, fixed their bayonets and conducted a series of charges and countercharges against the advancing British forces. Under this cover, the remainder of the force on Long Island would withdraw to safety.[7]

The delaying action was effective, but the cost to the Maryland Battalion was tremendous. The “Maryland 400,” as history would label these men, bore nearly 80% casualties. A shattered remnant of the unit withdrew and joined the army in Brooklyn, but it was a shell of the once proud battalion. Just two nights later, on August 29th, the Continental Army withdrew under the cover of darkness to Manhattan. The stand of Gist and his 400 had earned widespread fame in the Continental Army, and it is said that Washington, viewing their action, remarked, “My God, what brave men must I lose today!” The performance of the Maryland Battalion at Long Island cemented their legacy as a fighting force. Without their bravery, the fight for American Independence may very well have ended that summer in New York.[8]

The battered remainder of the Maryland Battalion would continue their campaign with the Continental Army over the next trying year. They would stand with Washington at the Battle of White Plains, where Colonel Smallwood would be twice wounded by enemy fire.[9] In the winter of 1776-1777, they slogged with the Army from Trenton to Princeton in the Ten Crucial Days that again preserved the Revolution. That winter, the 100 remaining Marylanders of the battalion were joined by fresh recruits. Using the cadre of men left as officers and NCOs for the new units, the “Maryland Line” was born, expanding to the 1st and 2nd Maryland, later joined by five additional Maryland Regiments.[10] At Brandywine and Germantown in 1777, the Marylanders proved their worth and skill as veterans.

As the British Army shifted its operations to the American South in 1780, the Maryland Line was dispatched to reinforce the Continental Army under Major General Horatio Gates. At Camden in August of 1780, the Continentals again met disaster, but the stalwart Marylanders performed so well that Congress issued a resolution thanking “Brigadiers Smallwood and Gist, and to the officers and soldiers in the Maryland and Delaware Lines… for their bravery and good conduct displayed in the action…near Camden.”[11] The Marylanders, often affectionately referred to as “The Old Line,” again demonstrated their worth in fierce actions at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse, where the American defense was firmly anchored on the Maryland Line. In both these actions, they helped bring about battlefield success and cemented their role in the eventual American victory. [12]

As the war ended in 1783, the survivors of the Maryland Line returned home and began building a new nation. Maryland veterans became politicians, businessmen, artists, and educators. Many continued service in the militia and veterans of “The Old Line,” like Samuel Smith and Gassaway Watkins, would play prominent roles in the second fight against the British in 1814. Today, the legacy of the Maryland Line is carried on through its descendant unit, the 1st Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment. Their colors proudly bear the campaign streamer earned by the charge of the Maryland 400 at Long Island, alongside 23 others earned in the nation’s battles in the 250 years since that fateful day.[13]

[1] John Mack Faragher, ed., The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America (New York: Facts on File, 1990), 7, 31, 257.

[2] Society of Cincinnati, Maryland in the American Revolution (Washington D.C.: Anderson House, 2009) 1.

[3] “The Burning of the Peggy Stewart,” (Maryland Center for History and Culture) https://www.mdhistory.org/the-burning-of-the-peggy-stewart/

[4] John Conradis “The Baltimore Independent Cadets, 1774-1775” Military Collector and Historian, 252; Joe Balkoski, The Maryland National Guard: A History of Maryland’s Military Forces 1634-1991, (Maryland National Guard, 1991),5.

[5] Balkoski, The Maryland National Guard, 5.

[6] Craig Symonds A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution (Savas Beatie, California: 2024) 27.

[7] Symonds, A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution, 27.

[8] Balkoski, The Maryland National Guard, 5.

[9] David Hackett Fisher, Washington’s Crossing, (Oxford University Press, 2004), 110-112.

[10] 175th Infantry Regiment Lineage and Honors, U.S. Army Center of Military History.

[11] Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington DC: The Rare Book Shop Publishing, Inc., 1914), 249.

[12] John Kilbourne, A Short History of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army (Baltimore: The Society of Cincinnati of Maryland, 1992), 43; Symonds, A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution, 91.

[13] 175th Infantry Regiment Lineage and Honors, U.S. Army Center of Military History.