By SFC Aaron Heft, Historian, 111th Infantry Regimental Association

As a Quaker settlement, Pennsylvania was among the last American Colonies to establish a standing militia. During early European conflicts on the continent, British authorities called levies of Pennsylvanians into military service for the duration of the crisis or campaign, and at its close, they would be discharged and return to civilian pursuits. Though Quaker leaders preferred this form of service, some Pennsylvanians felt that pacifist leanings had left them “thus unprotected by the Government under which we live, against our foreign enemies that may come to invade us.”[1] On November 21st, 1747, a group of men met in Walton’s Schoolhouse in Philadelphia to remedy this situation.

As the so-called “War of Jenkins Ear” threatened cities along the eastern seaboard, many of Pennsylvania’s growing merchant class felt the need to address the lack of security by forming their own self-equipped and self-trained militia force. Under the leadership of Benjamin Franklin, alongside prominent Philadelphians like William Allen and Richard Peters, these men drafted a call for a “military association” modeled after those found in England at the time.[2] After circulating their proposal and appealing to citizens at several public meetings, Franklin published the Articles of Association in December 1747. On December 7th, 600 volunteers marched to the Philadelphia Courthouse and presented themselves to the city council. Informed by President Anthony Palmer that their “efforts were not disapproved,” on that chilly day at the corner of 2nd and Market Streets, the “Philadelphia Associators” were born.

by Robert Feke

(Courtesy of Harvard University

Portrait Collection, Bequest of Dr. John Collins Warren)

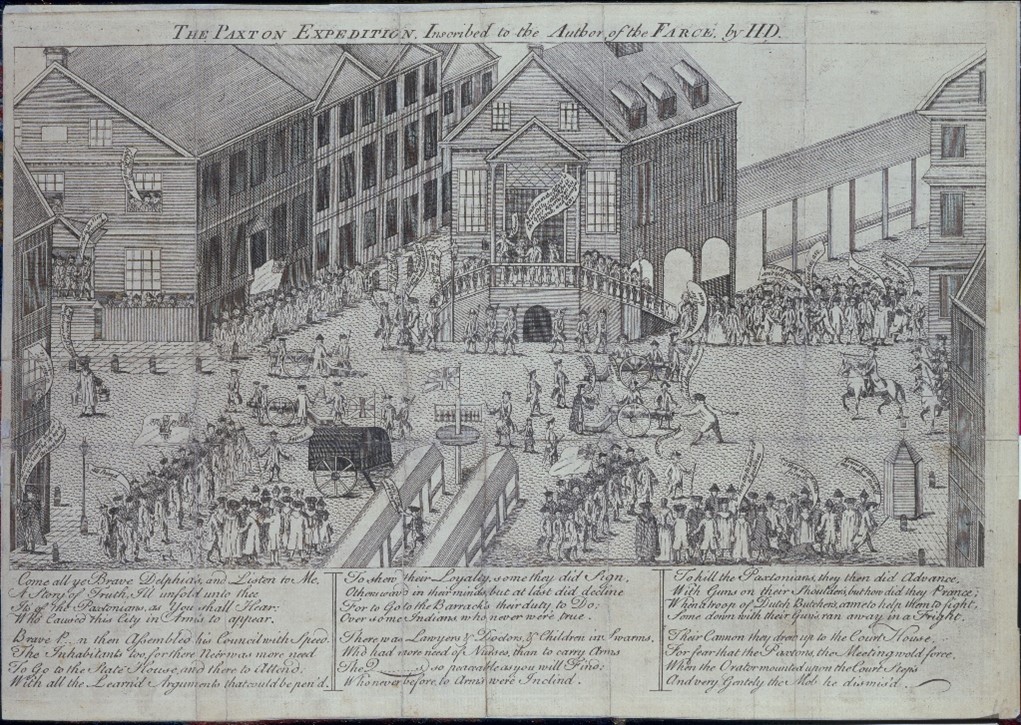

Over the next several years, the Associators expanded and professionalized. They established a grand battery on the Delaware River, trained artillerists, erected several fortifications, and inspired the recruiting and fielding of Associator companies in Bucks, Chester, and Lancaster Counties.[3] During the French and Indian War, the Associators had grown into multiple battalions, and several had volunteered as individuals to fight alongside crown forces in the western portion of the state. Back home, significant funding was put into reinforcing the city’s fortifications, arming the Associators with modern artillery and muskets, and protecting the city from both internal and external threats.[4] In 1764, during the crisis surrounding the uprising of the “Paxton Boys” in the western portion of the colony, the Associators were mustered into service. They provided a crucial deterrent for those who wished to undermine the government of Philadelphia.[5]

(Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia)

When revolutionary fever hit Philadelphia in the 1770s, many Associators were at the forefront of the movement. John Nixon, commander of the 3d Battalion of Philadelphia Associators, was active in the Committee of Correspondence and Committee of Safety. The Dock Street community elected Benjamin Loxley, longtime Associator Artillerist and community leader, to their Committee of Safety in 1775.[6] With the withdrawal of British troops from Philadelphia in 1774, the city’s Associators began openly drilling and recruiting in support of the American cause. The units attempted to standardize arms, consistently uniform their battalions, and upgrade fortifications in the city. But while volunteers from the Pennsylvania rifle companies marched north to join General Washington outside Boston in 1775, the city’s Associators remained in Philadelphia. There, they continued to support the patriot cause, and on July 8th, 1776, a Philadelphia Associator, Colonel John Nixon, read the fledgling nation’s Declaration of Independence publicly for the first time.[7]

The first major battlefield test would come to the Associators in the winter of 1776 on the frozen fields of New Jersey. Though the Continental Army had fought well for the past year, it suffered a string of defeats in the campaigns in New York, losing the central city to British forces. Washington’s army had withdrawn to New Jersey, but with enlistments waning and support for the Revolution faltering, he would need to perform dramatically to right the path to victory. His army would find this salvation in a surprise attack across the frozen Delaware River in the early hours of Christmas Day 1776, during a time when 18th-century armies generally settled into winter quarters to wait out the foul weather. On the dark night of December 25th, his forces crossed the Delaware in boats and delivered a brilliant defeat of the Hessian garrison. With nearly 1,000 prisoners taken at the cost of half a dozen casualties, Washington and his men withdrew back to Pennsylvania, leaving their enemy stunned and their cause reinvigorated.[8]

Though the Associators had taken part in the operation, they had not seen active combat in the action. In fact, due to a second crossing made by Associator units, Washington gained valuable intelligence that spurred his next move. A few days after success at Trenton, Washington repeated his gamble and crossed the Delaware again to engage the enemy. Associators and their comrades arrived on the streets of Trenton, took up positions along the Assunpink Creek, dug earthworks, and prepared for an attack by an approaching column of British and Hessian troops. On January 2nd, British forces launched an assault on their positions but were driven back. Realizing the danger to his front, Washington again gambled with an audacious plan. He withdrew his men quietly from along the creek and marched north to Princeton under the cover of darkness.[9]

In the early morning hours, his men encountered a British column and swiftly attacked the garrison remaining there. The Associators, making up the bulk of Washington’s force, were quickly in the thick of the fight. Confusion on the battlefield and losses of leaders like General Hugh Mercer threw the attack into disarray. In this moment of crisis, General Washington rode forward on his horse into the close combat, shouting to his men, “Parade with us, my brave fellows, there is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly.”[10] With that call, the Associators again charged forward, driving the British from the field through the streets of Princeton and capturing the remainder of the garrison there.[11] This early morning action by a group of Pennsylvania militia outside of Princeton ended what many historians refer to as the 10 Crucial Days, the actions that saved the American Revolution.

(Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

The Associators would not hang their hat on the military legacy of Princeton. They would soldier again during the battles of Brandywine and Germantown, supporting Washington’s Army in some of the darkest moments of the Philadelphia Campaign. Many Associators would volunteer for service with the army in later campaigns, providing skilled cadre for Pennsylvania regiments. In the post-war years, the Associator spirit remained with the Pennsylvania Militia. As the size and shape of Pennsylvania’s forces evolved over 250 years into the modern National Guard, so too did the Associator Battalions. Today, the Pennsylvania National Guard fields two units descended from the troops who fought under Washington that victorious day at Princeton: the 1st Battalion, 111th Infantry, descended from the Associated Regiment of Foot, and the 103d Engineer Battalion, descended from the Associator’s Train of Artillery. Today, as we celebrate the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution, men from these units are deployed as part of “Task Force Associator,” defending the nation’s interests once again.

[1] Benjamin Franklin, Form of Association, 24 November 1747, accessed through: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-03-02-0092

[2] Samuel Newland, The Pennsylvania Militia: Defending the Commonwealth and the Nation: 1669-1870 (Annville: Pennsylvania National Guard Foundation, 2002), 35, 37-38

[3] Joseph Seymour, The Pennsylvania Associators, 1747-1777 (Westholm: Yardley, PA, 2012), 49-51.

[4] Seymour, The Pennsylvania Associators, 66.

[5] Seymour, The Pennsylvania Associators, 112-116.

[6] Seymour, The Pennsylvania Associators, 134-135.

[7] Chris Coelho, “The First Public Reading of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 1st, 2021, accessed at: https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/07/the-first-public-reading-of-the-declaration-of-independence-july-4-1776/

[8] Symonds A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution, 31; Samuel Smith, The Battle of Trenton (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2010), 25

[9] Symonds A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution, 33; “A Fine Fox Chase: The Battle of Princeton,” Finding the Maryland 400, 3 January 2014.

[10] Sergeant R___, “The Battle of Princeton,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Vol. 20, No. 4:1896), 517.

[11] Symonds A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution, 33; “A Fine Fox Chase: The Battle of Princeton,” Finding the Maryland 400, 3 January, 2014.