By Kevin Brown

We frequently receive requests here at the National Guard Memorial Museum from historians and relatives of guardsmen for assistance with service records. However, this isn’t always easy due to a devastating 1973 fire that impacted military service-related documents at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). The fire, which affected the Federal government’s St. Louis archival site, was unprecedented in damage to military history preservation efforts.

The Federal government created the National Archives and Records Administration in 1934 as a New Deal-era project to centralize the nation’s growing historical document collection. The Truman and Eisenhower presidencies further reformed the National Archives to accommodate the massive influx of military service records representing America’s growth into a global power. The agency was placed under the General Services Administration in 1949, centralizing all defense-related service records (including National Guard ones) into the National Personnel Records Center-Military Records Center (NPRC-MPR) in 1955.

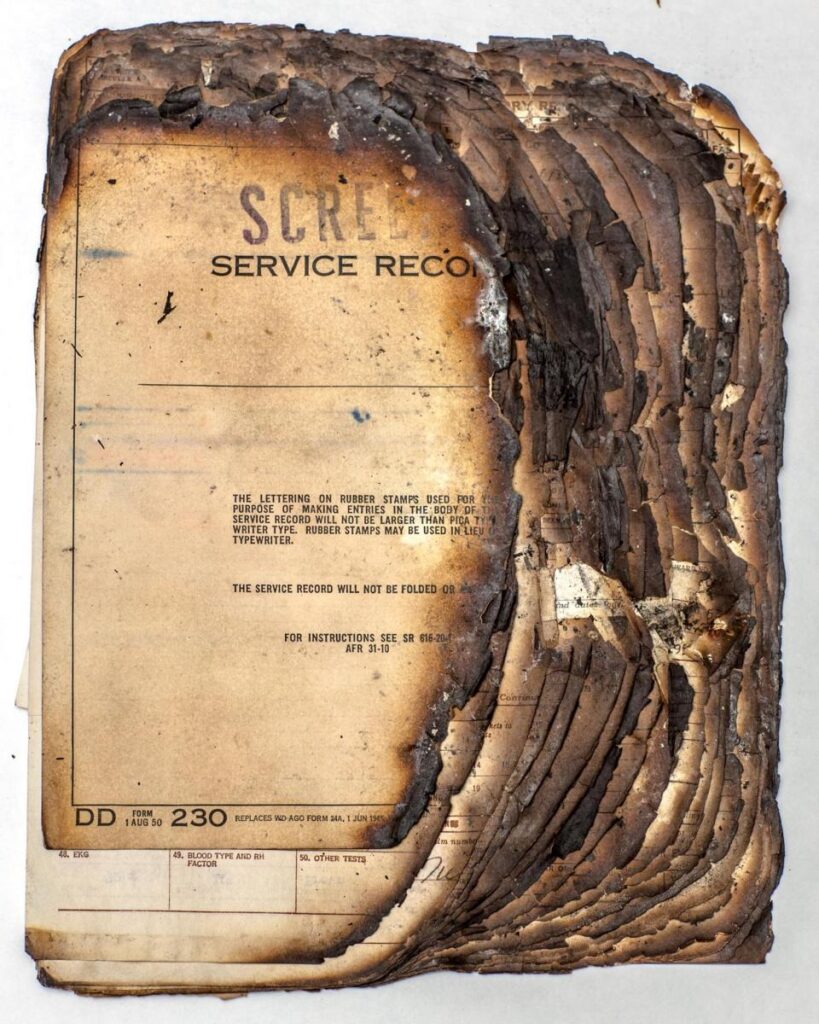

(Courtesy of the National Archives)

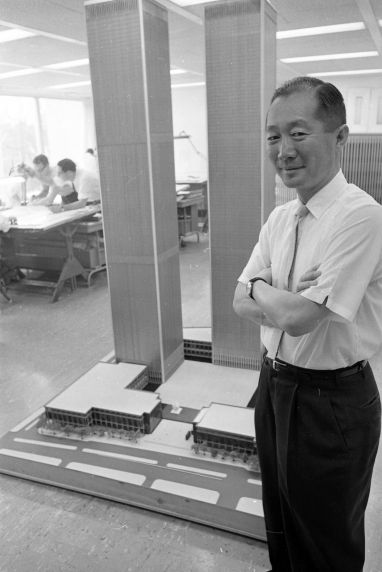

The GSA chose the St. Louis suburb of Overland, Missouri, as the agency’s military records location, with future World Trade Center architect Minoru Yamasaki as the head designer. Yamasaki designed the St. Louis military records buildings in the brutalist style, a design form considered futuristic and cheap to construct. These factors made Brutalism a popular post-war architectural design style for other public works projects like low-income housing, mass transit hubs, and office buildings.

Department of Defense officials advised against installing a sprinkler system during NPRC-MPR’s construction. Professional archivists regard water damage and mold growth as destructive as fire. NPRC contained flaws such as a combined office and warehouse layout with large areas lacking fire retardant walls. A lack of safety provisions, open spaces without fire-resistant walls, and copious stored paper records made the St. Louis archival site dangerously vulnerable to fire. In the years leading up to the 1973 fire, federal officials determined that fire risks warranted installing a sprinkler system in all future archival sites.

(Courtesy of the Walter P. Reuther Library)

NPRC-MPR opened to the public in 1955 to ensure veterans could obtain needed service records. NPRC-MPR also stimulated federal job opportunities outside of Washington D.C. for St. Louis residents. NPRC’s mission became vitally crucial with the Federal government’s further expansion designed to meet the needs of the millions who transformed American society through their service in World War II.

Emergency dispatch centers received reports of a fire shortly after midnight on Thursday, July 12, 1973, at 9700 Page Boulevard in Overland, Missouri- the Military Personnel Record Center location. Even though firefighters responded within minutes, the archival fire was so intense that emergency personnel could not locate the fire’s source. Early-stage efforts to extinguish the flames by piping water into the archives via snorkels proved unsuccessful, and the blaze only intensified.

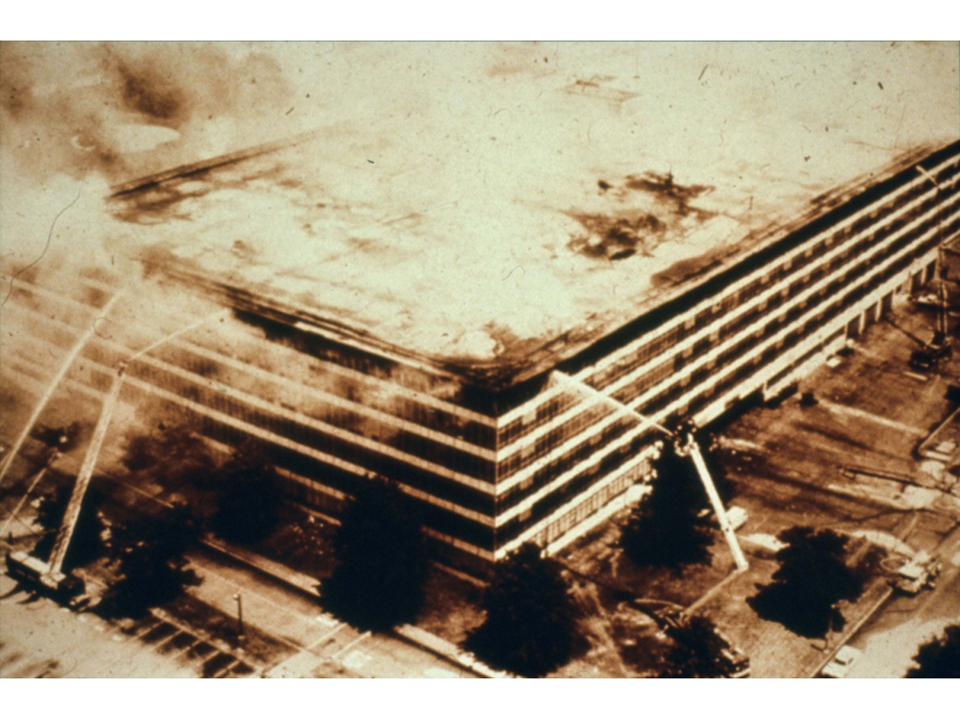

(Courtesy of the National WWII Museum)

Over 42 St. Louis area fire districts were involved in the efforts to extinguish the military personal records fire by 1:00 AM. However, the fire within the federal complex had become too intense by this time, and most firefighters had to give up all internal firefighting activity for safety reasons by dawn. Low water pressure continued to plague the responding fire departments despite repeated calls to the water company to increase pressure. Other problems arose, impacting the emergency response over the next 24 hours, such as equipment failures and the discovery that the fire had spread much further throughout the complex than initially thought.

By July 16, first responders eventually suppressed the fire that engulfed NPRC by summoning a constant water flood. The end of firefighting meant that only the first of the Federal government’s fights were over, as the destruction impacted millions of veterans. Inspectors determined that Army and Air Force records covering 1912-1959 suffered the heaviest damage.

The U.S. government had taken steps to mitigate damage since the fire had started, including halting all mail requests along with a directive ordering agencies to suspend record disposal. Firefighters had managed to save essential items from the site of the federal records, such as computer tapes which served as a vital finding aid.

The fire impacted veterans who relied on the federal records system to access health care services, pensions, and job verification. The 1973 fire hindered WWII and Korean veterans’ families’ efforts to obtain survivor benefits as these elderly servicemembers rapidly pass away. The destruction of NARA’s service records has also obstructed genealogists attempting to trace family history, providing frustrating dead ends for those engaging in this growing hobby.

The NARA archives fire in St. Louis has also impacted the work of the National Guard Memorial Museum. The fire destroyed the biographical information of well-known guardsmen from before World War I through Korea, making our work for these momentous historical eras more challenging. This fire has complicated additions to the museum’s famed Medal of Honor gallery chronicling the heroic feats of guardsmen who received the nation’s highest military decoration. The staff has difficulty verifying potential candidates’ National Guard service since their original records were lost. We also frequently hear from the descents of World War II-era guardsmen who encounter the same problem when researching their family history.

Unfortunately, the 1973 military records fire was not the only serious incident at NARA. Five years later, in 1978, a similar fire broke out at the agency’s main service center in Suitland, Maryland, destroying early Hollywood films and footage from the Great Depression and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

These two devastating fires within a decade prompted further changes at the National Archives, becoming a disaster management industry leader. NARA has also worked with critical primary source material creators like the armed services and entertainment industry to find replacements for lost material when possible. Other accidents have occurred at NARA sites after the 1970’s fires. However, NARA averted severe damage in these instances through the previous devastating lessons. Today, the National Personnel Records Center-Military Records Center is based out of Spanish Lake, Missouri, only miles from its previous location in Overland. NARA now houses military records in a modern facility, digitizing all items to prevent loss and maintain organization.